Moby-Dick Recap: Etymology, Extracts, and Chapters 1-2

Also, what is up with that Dedication Page, Melville

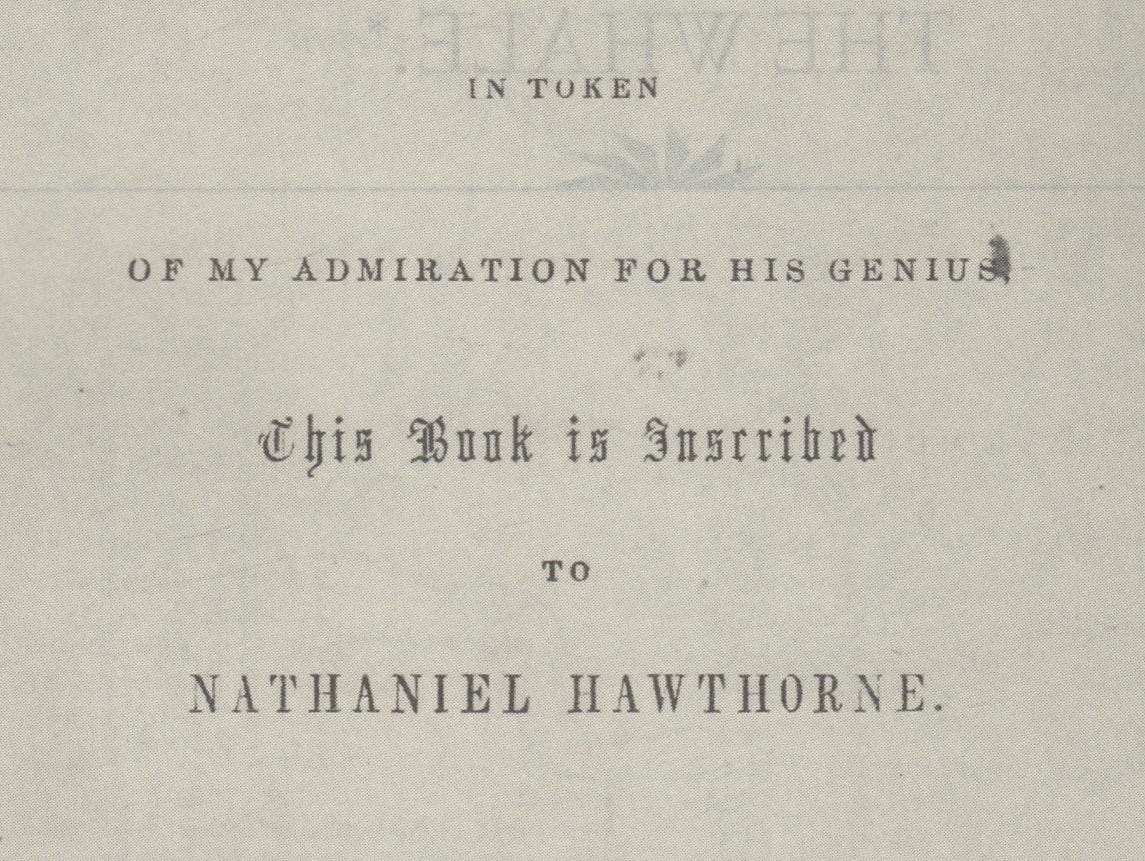

Technically, the first words of Moby-Dick are not the famous “Call me Ishmael.” No, before Chapter 1, we have these two weird sections called Etymology and Extracts, of which the opening sentence is “The pale Usher—threadbare in coat, heart, body, and brain; I see him now.” I’ll discuss Etymology and Extracts, but first, I want to address some words that come even before those opening sections. I’m talking about the dedication page, which is:

Nathaniel Hawthorne, of course, being the author of The Scarlet Letter. Ahem, let’s talk about this dedication page for a minute.

Moby Dick Summer will be my first time reading Moby-Dick, but it was assigned in 11th Grade Honors English. 16-year-old me started it, but once the Pequod set sail, I’ll admit I got bored and hit the Cliff Notes hard (there was also some copying of friends’ homework). So yeah, I didn’t really read it and I don’t remember much of what little I did, but if there’s only one thing I remember, it’s this dedication page. Look, back in high school, me and my queer friends read that "in token of my admiration for his genius" bit and were like lol Melville is totally in love with Hawthorne and the dude’s got no chill. We were cocky honors students with absolutely no proof of this, but when I revisited this as an adult, it appears we were far from the only ones who had this theory and there is actually some strong evidence on the matter. Please refer to History’s Dick Jokes: On Melville and Hawthorne or 5 Reasons to Believe Herman Melville Loved Nathaniel Hawthorne or Herman Melville’s Passionate, Beautiful, Heartbreaking Love Letters to Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Following this unrequited dedication page, we have these two curious sections called Etymology and Extracts. Etymology opens with this poor, tuberculosis-afflicted, assistant schoolmaster lovingly dusting his old grammar books. Then we get a few quotes about the etymology of the word whale and the importance of not forgetting the silent ‘h.’ And we learn how to say whale in a bunch of languages. I’ll throw in a few Google Translate-assisted more. Korean: 고래 (golae). Russian: кит (kit). Arabic: حوت (hut).

The next section is called Extracts and it has even more quotes. The section begins with the explanation that the quotes were compiled by this put-upon character called the sub-sub librarian. I’m somewhat amused by the inclusion of this, they were obviously compiled by Melville himself.

(In general, I always find it funny when authors of older books create this fictional framework to rationalize why the text of their novel exists. It always has to be some found document with some made up little story introducing how the document was found, and it feels way faker than simply believing that a novel is a character’s translated consciousness or whatever readers are able to accept today.)

Anyway, the “sub-sub librarian” drops, like, eighty quotes about whales from a variety of sources. Most of the quotes pertain to how large and destructive the body of a whale is. We have whales rushing boats and forcing the sailors to leap overboard. We have whales falling on people and killing them instantly. We have quite evocative quotes about whales’ gushing gallons of blood and brain-damaging bad breath. A couple of the quotes are a bit of a stretch. Or, as my friend Carly said, when we were texting about this section, a few kinda feel like ‘here’s that’s one time in hamlet where he says ‘whale.’”

Overall though, Extracts really grew on me. For a novel about obsession, fronting your book with eighty epigraphs all circling the same themes sets a vibe.

After the eighty obsessive whale quotes, we finally get to Chapter 1 and “Call me Ishmael.” As someone who really fixates on short sentences, as well as the sound of sentences, or even the way certain letters look next to each other, I really do get the hype about this famous opening line. There’s something about it being imperative, its sole three words, all those consonants. For a first sentence, it has more bite than, say, “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

Also, there’s more going on in those three words than you might think. Why is he demanding we call him Ishmael, this name with heavy biblical implications, anyway? Is it because his name is not actually Ishmael? Sus. Perhaps the narrator just chose that as his pseudonym, preferring to remain anonymous. Or is he actually a stand-in for Melville himself, who also went on whaling voyages? Is Moby-Dick autofiction? (Lol, jk, I am not going there.)

This ambiguity is even conveyed in a baby book. My aforementioned friend Carly shared Jennifer Adams’ Moby-Dick with me, a board book with cute illustrations by Alison Oliver. In the picture below, Queequeg, Daggoo, Stubb, and Starbuck’s names are included next to them, but check out how our favorite narrator is labeled.

After possibly telling us his name, Ishmael explains that whenever he’s feeling depressed, he takes to the sea. Well, depressed might be too subtle a word for it. Our boy Ish feels straight up suicidal or homicidally violent whenever he’s away from the ocean too long. And even if you, uh, can’t quite relate to that, he believes we all feel, to some extent, the mystical call of water. Think about how we all love going to the beach or local lakes. Why do people congregate around Battery Park? Because it’s at the tip of Manhattan right near all the water. Would Niagara Falls be a wonder of the world if it was a pile of sand? I don’t think so!

And when Ishmael takes to the sea he does so in what he believes to be the purest way—as a simple sailor. Not as a passenger, there’s something too moneyed and corrupt in that. After some stints as a merchant sailor, he decided to go on a whaling voyage, which is the story he is about to tell us. It was a journey he believes he was fated to be on, nor could he say no to the excitement of chasing whales, those fearsome creatures. I really dig the foreboding tone of this chapter’s last line, how it teases Moby-Dick himself, referencing him, but not by name: “and, mid most of them all, one grand hooded phantom, like a snow hill in the air.”

After this great setup, in Chapter 2, we are off. Packing light, Ismael heads to Nantucket. He misses the sole boat out to Nantucket so he has to stay overnight in New Bedford. There’s some whaling ships that leave out of New Bedford, but he’s dead set on Nantucket, believing it to be the most authentic experience or something. He passes by a few inns that aren’t in his budget, mistakenly enters a Black church, before settling on The Sprouted Inn. It looks a little dilapidated, the sign has a “poverty-stricken sort of creak” and the owner’s last name is Coffin, but he’s tired and there aren’t a lot of options. Maybe it’s that type of rundown place that has character and coffee that tastes cheap, but like, in a good way? Guess we’ll find out in Chapter 3…

PS: Next time someone tells you they’re considering leaving New York (due to rising rents, wanting more space, the noise), just reply, “Mmm, sounds like it’s time for someone to quit the good city of old Manhatto.”

Enjoyed this recap muchly! I have an annotated copy of the book, but this commentary's actually opening the story (and particularly the introductory sections) better for me.

For all the giggling my friends and I did in school about the title, those Hawthorne commentaries led me to look up the etymology for the slang term "dick." Apparently it didn't become a euphemism for "penis" until the 1880s, a few decades after this was published. But "dick" *was* a term in the 17th century for a male sexual partner, so maybe we weren't so wrong to giggle.