Moby-Dick Recap: Chapters 3-8

Queequeg, Queequeg, Queequeg

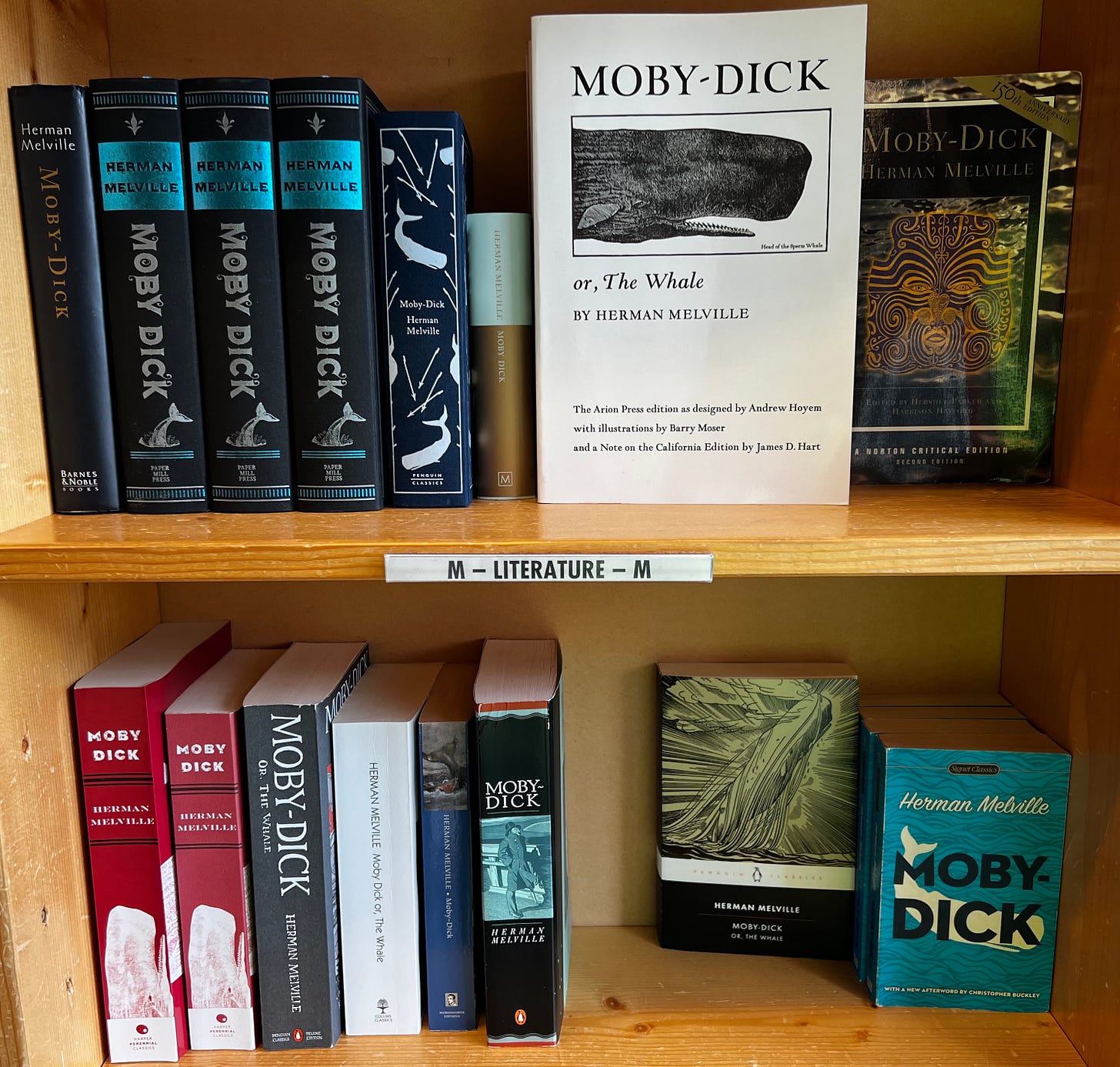

Earlier this week, I was in Portland, Oregon and swung by Powell’s, the city’s famous bookstore. Check out how many different versions there were of Moby-Dick.

I want to call particular attention to the edition in the top right, which features an engraving of Te Pēhi Kupe, the real-life inspiration for Queequeg, a character who is introduced in Chapter 3 and will be the primary focus of this recap.

But before I share my thoughts, Moby Dick Summer has over 200 subscribers and I’d love to hear from you all. Please introduce yourself and share what’s driving you to read or re-read Moby-Dick. Or if you’d prefer to engage with some questions related to Chapters 3-8, I’ll ask some at the end.

In “Moby Dick in 2020,” an episode of the Open Source podcast, the writer Jonathan Lethem says, “one of the great things about Moby-Dick is the way it reverberates in culture. You know it before you know it. Most people don’t think necessarily that they even want to read Moby-Dick, but they kind of learn about it anyway… you sort of find yourself absorbing little pieces of it. It’s there waiting for you.”

Basically, long before you’ve read the novel, you’ve absorbed references from all over: Star Trek quotes it, The Simpsons spoofs it, a supporting character’s name is used by the biggest coffee conglomerate in the world. Ahab comparisons abound to nearly every political leader or CEO who has ever had an obsessive or fanatical pursuit. Steve Jobs is Ahab. Obama’s Ahab. Personally, I find many of those comparisons too predictable, or too easy. A few academics make Ahab/Trump comparisons in “Moby Dick in 2020” and it is the most dated part of the podcast.

Another cultural reference—the first time I ever heard the name Queequeg was in The X-Files. I was a huge fan of the show growing up and it’s the name Dana Scully gives her pet Pomeranian. Here’s a bit of dialogue between her and Mulder in the episode “Quagmire:”

MULDER: Why did you name your dog Queequeg?

SCULLY: It was the name of the harpoonist in Moby-Dick. My father used to read to me from Moby-Dick when I was a little girl, I called him Ahab and he called me Starbuck. So I named my dog Queequeg. It's funny, I just realized something.

MULDER: It's a bizarre name for a dog, huh?

SCULLY: No, how much you're like Ahab. You're so consumed by your personal vengeance against life, whether it be its inherent cruelties or mysteries, everything takes on a warped significance to fit your megalomaniacal cosmology.

MULDER: Scully, are you coming on to me?

This conversation continues, and it ends with Mulder quoting a line from Moby-Dick (“Hell is an idea first born on an undigested apple-dumpling”) essentially revealing that he knew the origins of Scully’s dog’s name the whole time. Oh, it’s a famously flirty scene between the two of them, known in X-Files fandoms as “the conversation on the rock” or TCotR. Okay, we’re getting off track here, I’m going to steer this ship away from my X-Files obsession and back to Moby-Dick, but the point made by Jonathan Lethem stands. You have a lot of ideas about what Moby-Dick is about before you actually read the book.

Queequeg’s first appearance in Chapter 3 is hyped with anticipation. The landlord messes with uptight Ishmael’s anxiety over his future bedmate (see: the whole “can’t sell his head” exchange). Ishmael reluctantly tucks in for the night, then hears “a heavy footfall in the passage” and sees “a glimmer of light come into the room from under the door.” This is classic, nearly cliché imagery that signals the arrival of someone to be feared, but Ishmael comes to a major realization as this scene unfolds. As he hides under the covers, watching Queequeg get ready for bed, Ishmael understands that “he has just as much reason to fear me, as I have to be afraid of him.” By the end of the chapter, he’s waking up next to Queequeg and declaring that he’s never slept better in his life. Indeed “ignorance is the parent of fear” is as evergreen a statement as ever.

In my own cultural bank of Moby-Dick knowledge, I already knew that Queequeg was a beloved character. And also, that in the time Melville wrote him, there weren’t many characters of color written in American literature with such depth and humanity. But crucially, he’s not simply a receptacle for empathy. He’s a cool, “as cool as an icicle,” a character you want to be. You don’t want to be uppity Ishmael, you want to be Queequeg, sitting at the head of the table at breakfast, spearing steaks with his harpoon like he has no fucks to give.

Sure, if you’re reading it today, it’s not perfect representation, there’s certainly things to critique. In “Moby Dick in 2020,” Lethem acknowledges that. Here he is talking about the racial diversity of the Pequod crew:

“Melville doesn’t get all the way there. There are all kinds of incompletenesses and stumbles. And in many ways, the white characters are given a much greater delineation. It’s almost as if he can idealize the multicultural, but he has trouble particularizing it, right? So, it’s sort of there, it’s evoked, it’s brought into view, and then he ends up talking about Stubb and Flash and Starbuck a whole bunch. The dream is there and I think the dream is kind of alive in the book, that this could be some sort of vision of a global multicultural apotheosis of human types… but this is why the book is so tantalizing. It seems to be dreaming of things greater than its author can even know.”

I’m really moved by that last sentence, because it articulates a quality I love in novels, or any art. Whether it’s made in 1851 or 2022, I’m skeptical of any piece of art that claims to have all the moral answers. What interest me more is the art that tries to be a better person, or imagine a better world, but still screws up a bunch. And the failing, the falling a little short, is where the beauty lies. It is also a generous act. If your work dreams of things greater than you can even know, you’re setting a path for future writers to pick up where you left off.

Alexander Chee is also interviewed in the Open Source episode and his segment is all about Queequeg. I’m going to save most of it for a latter recap, because there’s some spoilers, but I do love that Chee (one of my favorite contemporary writers, he wrote the excellent How to Write an Autobiographical Novel) is a big Queequeg fan. He’s even written some slash fanfic and has a Queequeg Tumblr.

Whether you full-on ship Quee and Ish (Quish?) or view their relationship as a buddy comedy, I’m excited to see where this aspect of the novel goes. Chee describes it as the emotional core of the novel, a love story. “We become interested in how this narrator is making sense of these people he has fallen in with,” he says. “And in particular, Queequeg is one of those people.” And how many novels can you name that feature a loving friendship between two men? It’s rare, even in contemporary literature today.

Shall I summarize the rest of this week’s readings? After the two cuddle all night, Ishmael just sorta watches Queequeg shave, get dressed, and get ready for the day (Chapter 4), then goes down to get breakfast himself (Chapter 5). He’s surprised how solemn and quiet all the whalemen are at breakfast, he expected them to be hootin’ and hollerin’ with wild tales about their time on the sea. Then he takes a little walk around New Bedford and tells us about the town (Chapter 6) before arriving at the whalemen’s chapel. Chapter 7 takes the morning’s solemnity even further, as Ishmael watches mourners visit memorial plaques that honor men who died at sea. Ishmael knows that his own name could soon be listed up there. Oh, and he also runs into Queequeg at the chapel, they exchange an awkward bro-nod. After some existential pondering, Ishmael watches Father Mapple get ready for his sermon, and this guy really lives for a dramatic entrance (Chapter 8). He climbs up a ladder to stand at a pulpit shaped like a ship’s bow.

All right, that’s it for today’s recap. Once again, a reminder to say hello in the comments. And as promised, some questions to engage with: what are your thoughts on Queequeg, or Queequeg and Ishmael? What references to Moby-Dick have you seen in the world that are totally wired and which are totally tired? And if you haven’t read the book already, any predictions about Father Mapple’s upcoming Chapter 9 sermon?

Hi! I'm Sabrina. I'm an early-career librarian and I have never read Moby Dick, even as an avid book reader and English major! I have been quite intimidated by it and have been told by many people to not read it because it is such a slog. I know we haven't gotten to the extensive whale anatomy sections yet, but so far I'm finding the writing surprisingly lovely.

Given it's prevalence in popular culture, I actually know very little about the plot and characters of the story. I knew nothing about the queer subtext before reading chapter 3 and I was absolutely delighted by it. They wake up spooning and don't get completely overwhelmed by no-homo energy. Amazing.

As a queer person, I feel like I am inclined to read queer subtext into a lot of things, but this was just so easy. Coming off the heels of watching Our Flag Means Death, I started picturing Ishmael as Rhys Darby's Stede Bonnet, which made the reading experience even more delightful. To me, Ishmael is quickly becoming a queer icon, only heightened by his intense melodramatic feelings about the ocean and wanting to hurl himself toward it.

I'm having a blast so far.

I subscribed awhile ago but didn't manage to keep up. These recaps are a lifesaver! Also: the Barnes & Noble version in the top left corner of your photo is the one I have, and it's pretty rad. Its typeface looks like it could be original! A real book nerd's choice.