We’ll get to the recap, but first, some housekeeping: next week is the last week of summer and it’s the last week of Moby Dick Summer too. We’ll have the last pages send on Monday and Wednesday, with a final recap on Friday. How is everyone feeling about its end?

I’ve also been considering how this Substack should exist after its all over. It will continue to exist online as a potential weekly reading guide for anyone who wants to read Moby-Dick, but following the model of the OG Dracula Daily, do I schedule it to run every summer? Or should I tackle another classic book in the same mode?

If I do the latter, it won’t be for a long while, but I’d be curious to know the other classic books that are on Moby Dick Summer subscribers’ to-be-read list.

Here’s some of mine:

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman by Laurence Sterne

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

Middlemarch by George Eliot

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens

The Diaries of Franz Kafka by Franz Kafka

Dead Souls by Nikolai Gogol

And here’s a few other classic books I’m interested in, but they’re published post-the 1920s, so they are not in the public domain.

The Waves by Virginia Woolf

Speak, Memory by Vladimir Nabokov

Jazz by Toni Morrison

Sula by Toni Morrison

Stoner by John Williams

What classics are on your list? The ones you’ve always wanted to read?

While you think it over, onto this week’s recap…

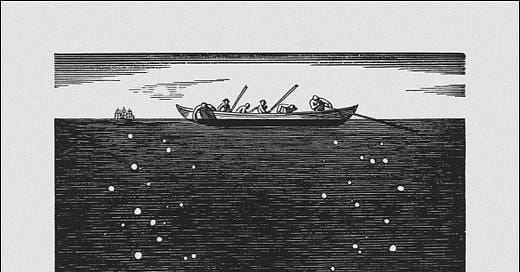

It’s the penultimate week of Moby Dick Summer, and man, almost every single chapter was full of death, doom, and foreboding symbols. Notably, not one of the chapters in this week’s readings was a non-narrative interstitial chapter. It was all plot, plot, plot, as the crew of the Pequod possibly rushes toward their own, um, plots—burial plots. And meanwhile, Ishmael’s disappeared into an omniscient narrator who can somehow be privy to Starbuck debating whether to murder Ahab (Chapter 123) and Tashtego asking the skies for rum in the middle of a typhoon (Chapter 122, the novel’s shortest chapter).

Yes, the Pequod survives that typhoon, and Starbuck descends to inform Ahab, who is sleeping in his cabin. After spying Ahab’s loaded musket, the same one he himself was threatened with, Starbuck goes into full Hamlet mode, debating whether he would be justified in killing Ahab to potentially save the crew. For some reason, I totally pictured Ethan Hawke as Starbuck in this moment, knowing that he has played both Starbuck and Hamlet in film adaptations (Starbuck even says, “Oh, my Captain! my Captain!” in a latter chapter).

Unlike the rest of the crew, Starbuck has been horrified by Ahab’s revenge-filled quest from the start. At this point, they’re all wary of his madness, well, possibly with the exception of Stubb, who, as recently as Chapter 121 was like, “Yeah, Flask, I know Ahab’s crazy, but a lot of ships and captains do crazy shit, we’ll be fine.” (Maybe he’s just hoping to have a nice slice of Moby Dick for dinner.)

But beyond that, no one’s chanting “Death to Moby Dick!” anymore, like they did when Ahab first revealed his plan and the doubloon reward. Yet, as is the case with many tyrants, no one—Starbuck included—is strong-willed enough to stop Ahab. He’s too charismatic, he holds too high a position of power, and like any dangerous leader, he has his inner circle of protectors (Fedellah and his crew). Ultimately, Starbuck puts back the musket.

The compasses don’t work (Chapter 124), an alternative method for navigation immediately snaps (Chapter 125), and still, Ahab, with “fatal pride” thinks he can bend things to his will. Pip appears, ranting about the self he lost overboard, and Ahab is moved by his madness. Game recognizes game, I suppose. He invites Pip to live with him in his cabin. I’d heard about the bond that is formed between Pip and Ahab, but I expected it to come earlier in the book.

Things continue to take a dark turn, with multiple bad signs in every chapter. The ship hears disturbing shrieks that sound like creepy wailing ghosts and Ahab’s all, “NBD, that’s just some orphaned seals crying for their mothers and vice-versa.” And then, an unnamed crew member falls overboard from the mast and dies. And strangely, no one even seems all that bothered by that. Everyone’s more worked up about the fact that the life buoy they tossed to him also sank and now has to be replaced. Queequeg says, “May I humbly offer my coffin that I’m not using anymore?” and the crew’s like yup, sounds good, let’s hoist up a symbol of DEATH for something that should be a symbol of LIFE. That’s how utterly fucked everybody’s feeling on this ship.

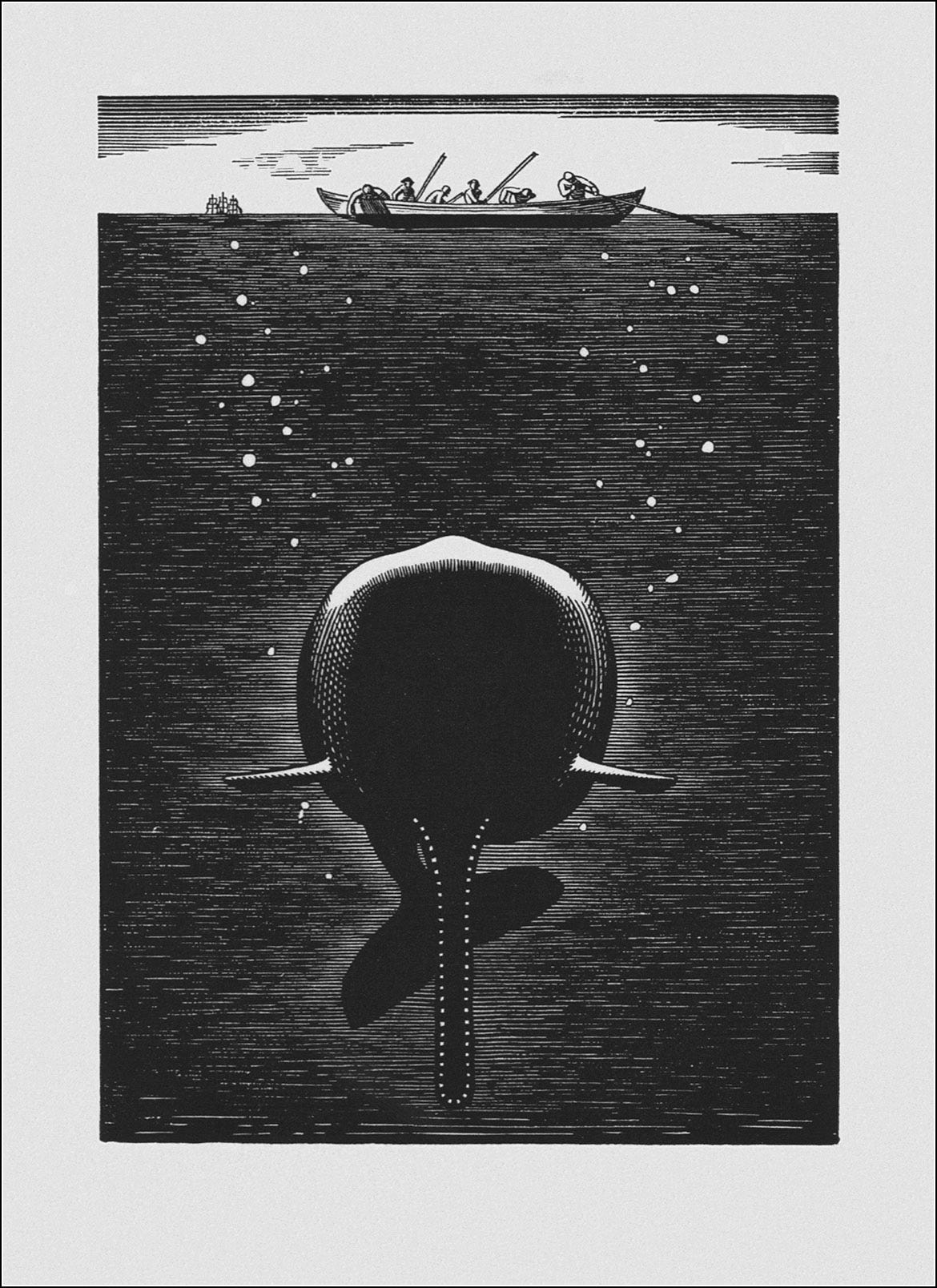

The Pequod encounters two final ships, the Rachel and the Delight. Ahab asks his signature question, “Hast seen the White Whale?” and the answers are now like, “Yeah, yesterday” or “Yup, saw him mere hours ago and he completely desecrated this whaling boat and killed half a dozen men.” In Chapter 128, the captain of the Rachel begs Ahab to help search for a missing boat his son was on, but Ahab coldly refuses, unwilling to lose a day when they’re so close to Moby Dick. It’s a bleak moment. Yes, gone are the comic and jolly encounters of ships past, like the run-in with the naive Rose-bud (Chapter 91), or party boat the Bachelor (Chapter 115), or any of the other vessels the Pequod has crossed paths with that might symbolize other ways to lead a ship, or um, a country?

Ahab loses his hat in what is seen as another bad omen, and then we have Chapter 132, “The Symphony” a moving chapter and an intensely satisfying one. Whether I’m reading classic literature or watching modern television, I always like the moment when the villain, or anti-hero, reveals a backstory, or inner life, that appeals to our sympathies. And it’s done beautifully here. Ahab laments to Starbuck about the forty years he’s spent mostly at sea. It’s been forty years of isolation, lack of fresh food, and time barely spent with his young wife (“I widowed that poor girl when I married her”). Ahab’s near sixty, and his monologue is full of regret and grief for how he has spent his life. He wishes not the same fate for Starbuck, and in a moment of rare selflessness, urges him to stay on the ship when they lower for Moby Dick.

It’s the last opportunity to turn around, and Starbuck pleads with him to give it all up and return to Nantucket. For a brief minute, it seems Starbuck gets through, they both envision the beautiful days Nantucket can have, and Ahab imagines his own boy waiting for him to return home. But that window soon closes, for the inevitable course this trope also takes is that the villain, after a moment of self-reflection and guilt, never gives up his destructive plan.

And we, as readers, never wanted him to anyway. After four hundred pages, the anticipation is high and we’re finally going to have our showdown—it best be fulfilling. Oh Moby Dick, I clutch thy heart at last.